-

Casa Triângulo is pleased to present Algaravia, the first solo exhibition by Andy Villela at the gallery, featuring critical texts by Carollina Lauriano, Clarissa Diniz, Lucas Albuquerque, Lorraine Mendes, and Victor Gorgulho.

Algaravia: A Portuguese word referring to a loud mix of many incomprehensible voices speaking at once. A babbling din, a cacophonous polyphony. No single English word fully captures the same range of meaning, which includes both the loudness and the unintelligibility of the overlapping voices.

The concept behind the exhibition Algaravia lies in the very meaning of the word: a tumult of voices, a jumble of words, or simply an incomprehensible foreign language. The idea is that we return to the debate around art, focused primarily on the artistic product in its own right, apart from the psychobiographical background of the artist – which does not, however, mean ignoring the entire narrative construction of the artist's journey, both in the market and in her social context. By encouraging commentary on the work in and of itself, we seek to shed light on the experience embedded within. The artwork attracts us precisely through its imperfections and contradictions, yet ultimately reveals itself only within the realm of language. Experience is where we connect as humans, while it is through the use of words that we attempt to decipher the intangible.The work of curators and researchers is crucial for the cultural dissemination of artistic productions, and words are their primary tool. However, language bears an inherent ambiguity, which can expand or limit a subject, event, or artist. Art is the space where we expect and even welcome multiple viewpoints that lead us away from fixed ideas or established concepts. May we have the courage to enter a state of novel creation and radical imagination, creating a babbling din of sounds that resonate with our time and place.

-

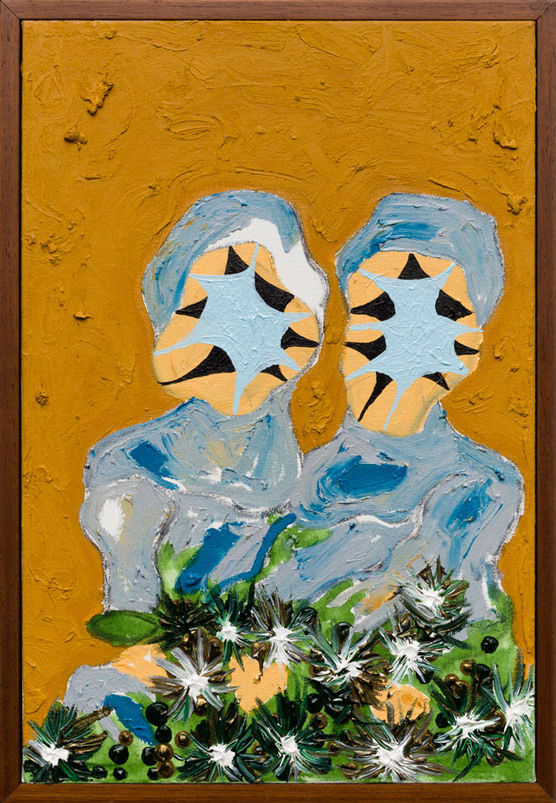

Algaravia I, 2024

Algaravia I, 2024 -

-

Algaravia II, 2024

Algaravia II, 2024 -

Poetry abandons science to its own fortune is my imaginary subtitle for Algaravia (2024). Borrowed from the book of photomontages Pintura em pânico (1943) by Jorge de Lima, this possibly prophetic line serves as a lens for viewing Andy Villela’s most recent painting.Despite the presence of gnostic symbols like skies, balance scales, stars, suns, moons, skeletons, lightning, and portals, the work’s cacophonous verbosity prevents me from seeing it as a celebratory allegory of knowledge. Instead, it suggests the idea of a science bereft of meaning—one that is so arrogant and narcissistic that even poetry, as stubborn and resistant as it is, has fled from it. It has thus remained as algaravia.It is therefore intriguing to learn that the triptych draws inspiration directly from the highly concatenated allegory The Virtues and Vices (1306), painted by Giotto di Bondone in the Cappella degli Scrovegni (Padua, Italy). With both works in mind, we notice Villela’s systematic effort to undo the rigid and assertive moral, social, theological, and aesthetic organization of the famous pre-Renaissance work. Like others of his time, Giotto was laying the foundation for what we, centuries later, consider to be “scientific thought.”In disrupting this order, Andy’s gesture seems to follow the “advice” attributed to the poet Rimbaud, cited by Murilo Mendes in the “Preliminary Note” of the aforementioned book by Jorge de Lima: “disarticulate the elements.” “Ultimately, this disarticulation of elements results in articulation,” Mendes explained when outlining the surrealist operations which, due precisely to their entropic spirit, “allow and facilitate the encounter of myth with everyday life, of the universal with the particular.”The disjunction that Villela brings about based on Giotto’s regulated-and-regulating painting therefore arises from the separation, fracturing and reassembling of its elements, which, by being so thoroughly disarticulated, are ultimately transmuted. Even if the voices of the ancient fresco can no longer be clearly understood in Algaravia, its diptych arrangement with symmetrical contours is still audible. Arising from the binary nature of the virtues/vices judgment, despite being dismantled, the memory of this allegorical dichotomy somehow survived the artist’s disassembly and, in the form of noisy, Babel-like statements, insists on remaining as a melodic vestige of something that was once there.Perhaps that something was science, which poetry – either for revering the chance portion of destiny or for being wise – had to abandon, at least in Andy Villela’s Algaravia.Clarissa Diniz

-

from the series “The sea and the possibility of zero gravity” , 2024

from the series “The sea and the possibility of zero gravity” , 2024 -

O Banquete, 2024

O Banquete, 2024 -

“(...) Liberation from Babel comes only through algaravia.” 1– Maria Filomena Molder, in Babel, Arabesco e Algaravia

Of uncertain origin, the Latin quotation “quod me nutrit me destruit” [that which nourishes me also destroys me] floats solemnly in the upper part of the composition of Algaravia, produced in Rio de Janeiro by the artist Andy Villela. Some researchers believe it to be a variation of an older spelling, with famous references found in the writings of English poet and historian Samuel Daniel or the sonnets of the playwright William Shakespeare. In the latter’s work, it appears in the play Pericles, Scene 2:SIMONIDES: What is the fourth?THAISA: A burning torch that’s turned upside down;The word, ‘Quod me alit, me extinguit.’SIMONIDES: Which shows that beauty hath his power and will, Which can as well inflame as it can kill.(SHAKESPEARE, 1611, Act II, Scene II)Echoing Simonides’ interpretation, but avoiding any naive pretension to beauty, Villela conceived a triptych to reflect on the contrasts and intricacies of her production. The young artist, whose interest in pictorial possibilities drives her work, conceived Algaravia as an experimentation with different techniques and genres, in which fragmentary images are woven together on canvas. The opaque scenes in the painting, constructed out of the dissolution of their own pictorial making, arise punctuated by a prevailing instability that prevents the composition from being attached in any particular style.The left canvas, with lighter tones, is constructed with greater attention to each fragment. Based on a rereading of the allegories in Giotto’s fresco series The Virtues and Vices (1304–1306), these figures are camouflaged in layers. These layers partially overlap the figures, or otherwise hinder their perception due to the proximity of their color with their surroundings. The first canvas in the triptych thus bears a set of elements that reflect on the human condition in Western art history. Their recovery, however, takes place through the ruination of their function in a gap-filled visual construction, making these figures more akin to exercises in composition than to instruments of moral reflection.In contrast, the two rightmost canvases are dominated by better defined shapes and a saturated palette. With its somber tone, the second act of Algaravia seems to echo the sonorous character of its title in the deep, gloomy meanders of its composition. Between recognizable representations and fluid beings, the relationship between figure and ground is demarcated by the salient use of solid colors. Even silence finds its place here – in the lower left scene, with its coloration and theme that recall the paintings of Edward Hopper’s taciturn phase, or, on the extreme opposite side, where the mouthless face suggests a streamlined interpretation of Ismael Nery’s geometric figures. The serpentine patterns weave the three canvases together, sometimes framing the outer edges, sometimes interconnecting the scenes.Going beyond the Petit Larousse dictionary’s definition of the term algaravia – “a bizarre, unintelligible language” – the artist shifts the pejorative aspect of the word, commonly directed at a foreigner who does not conform to the common language, to instead allude to the foreign as something that inhabits her own work. In a bold dive into dissonance, she runs counter to an art scene that values the ordering and categorization of artistic practice, instead setting out on a defense of multiplicity. In the course of her journey, it’s possible – and indeed likely – that certain practices seen here will solidify over time. Even so, it is to be admired that any such crystallization does not imply the suppression of experimentation for the sake of a set style. Algaravia is Villela’s ultimate expression on this path.- Freely translated by us.

Lucas Albuquerque

-

Sewing, from the series The sea and the possibility of zero gravity, 2024

Sewing, from the series The sea and the possibility of zero gravity, 2024 -

Untitled, from the series The sea and the possibility of zero gravity, 2024

Untitled, from the series The sea and the possibility of zero gravity, 2024 -

Untitled, from the series The sea and the possibility of zero gravity, 2024

Untitled, from the series The sea and the possibility of zero gravity, 2024 -

-

The Door, 2024

The Door, 2024 -

Mil intenções ocultas, 2024

Mil intenções ocultas, 2024 -

-

Untitled, from the series Viventes, 2024

Untitled, from the series Viventes, 2024 -

-

Untitled, from the series Vestígios, 2024

Untitled, from the series Vestígios, 2024 -

Mud Moon, 2024

Mud Moon, 2024 -