-

Over the years, Nino Cais (São Paulo, 1969) has been patiently refining the sculptural meaning of his poetic production. The exhibition that guides us under the sign of Clarão [Effulgence] is very evidently concerned with the expressive power of the body – the form of our presence in the world’s eyes. True to the objects of everyday life and to his intimate and formative repertoire (which includes Catholic and familial semantics), the artist presents us with a consistent group of works, combining symbols, utensils, words, balancings, drawings and compositions. In doing so, he underscores how art’s political condition is inherent in each and every artistic gesture. Such gestures, steeped in implicit content and not always manual, bear the ephemerality of presence and of memory.

-

Santa Ceia, 2023

Santa Ceia, 2023 -

Therefore, it would seem that Nino Cais’s art is defined mainly by three underlying thrusts: the evocation of a basis of feelings and memories that constitute his own personal history, his continued appreciation of the intuitive power of creation, and his unique view of the language of sculpture, which he has refined and broadened based on the historical tradition of Brazilian art and the experimental exploration of his own feelings through other media and materials. By considering this conceptual, tripartite basis we can get an idea of his bearings, the compass guiding his critical perception of artistic practice.

Cais understands art as a trade, craft or occupation, something that is developed on a daily basis and demands time, routine and practice. It’s not that reflection is absent. Rather, reflection is the symbolic and abstract thread uniting all his production – whether graphic, material, objectual or performative. His activity is therefore imbued with a strong sense of presence, in which the artist himself is seen to be continuously implicit. His appropriations and assemblages – practices that are indissociable from the body of his oeuvre – are direct outgrowths of his desire for presence and evocation in art.

-

-

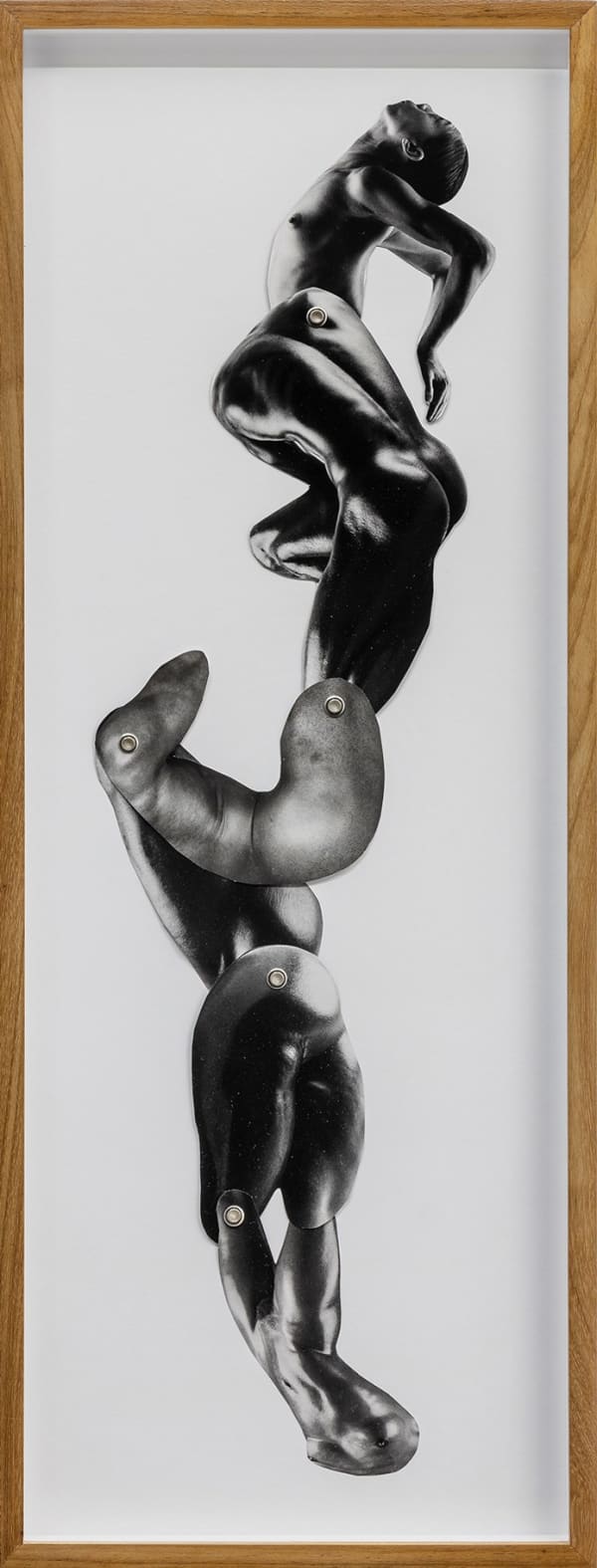

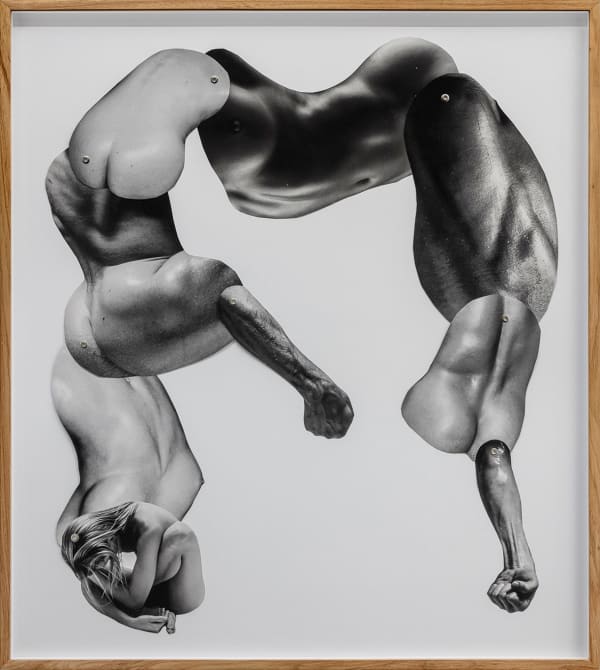

Untitled, 2023

Untitled, 2023 -

Sebastião (set of 3 works), 2023

Sebastião (set of 3 works), 2023 -

Verônica, 2023

Verônica, 2023 -

Untitled, 2023

Untitled, 2023 -

![Effulgence The exhibition is titled Clarão [Effulgence] for various reasons that shed light on the conceptual core of the artist’s...](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Rita, 2023

Rita, 2023 -

-

-

Ironically, it is something analogous to the artistic gesture itself – that which emanates from a creative myth. To be clear, I don’t want to say that this artist subscribes to this idea. Nevertheless, Cais has a keen perception of how Western art is deeply informed by the Christian values narrated in the biblical saga. In our long talks, he referred to the memory of Christ’s resurrection, and how it was immediately preceded by a blinding light, before the reembodiment of the crucified Son of God.

While it is temporarily blinding, the clarão is also a sign of opening and transformation: an intrinsic quality of art. When artists are thinking clearly about their creative aim, they can give image and/or form to their works. An example of such clarity in Nino Cais’s case is the chair object that is lent the quality of a ready-made. Twelve of them, made of wood and with different shapes, are suspended and tied with white shirts, and have a stack of white dinner plates on their seats.

Chairs found in secondhand shops, plates bought in housewares stores, and white shirts structure the sculptural pieces that compose his Santa Ceia [Last Supper] (2023). And, among two groups of six (an objective allusion to the 12 biblical apostles), there is a mirror that constantly reproduces the image of who is standing in front of the installation. It is a reproduction of the other, the one who is sharing the space of existence, which reverberates through the mirroring in the exhibition room. While Nino Cais’s poetics conveys a scholastic instruction, it also bears a Duchampian affiliation, which can be seen in the incisive and permanent reevaluation of the concept of the ready-made, an element present in art history since the second decade of the 20th century.

-

-

Querência, 2023

Querência, 2023 -

We can say that Cais’s action recalls dada operations involving ordinary series of everyday objects, especially the notion of the assisted ready-made, which Marcel Duchamp defined as an appropriated object on which the artist makes some change or intervention.[2] And after that procedure, the artist goes on to a second moment described as assemblage: a rich recombination of materials and objects imbue his work with countless meanings. An outstanding example of this is the sculptural piece in which a shovel – a par excellent symbol of labor – is “wearing” a shirt, whose sleeves are filled with wheat flour. That sculpture, titled Escavador [Digger] (2023), is a direct reference to Van Gogh’s lithograph depicting the simple, hard-working fieldhand.

The work Sebastião (2023) presents the same compositional dynamics: three sculptural pieces leaning against the wall composed of three speargun harpoons and three different dress shirts: one white, one black, and one red. In their extremely violent gesture, they very incisively imply the notion of presence, indicating paths which they also open. In his art, the use and meanings of tools, weapons and household utensils undergo a game of semantics. Certainly, this century-old practice – from the generative ready-made to the compositional assemblage – is the core of the enigma and refinement of Nino Cais’s artistic operations: a continuous operational exercise for subtly unveiling our presence in life.

[2] In his most recent publication, North American art critic Hal Foster reassesses this Duchampian concept for commenting on the latest appropriation operations in the art field. In that observation he begins by mentioning Jeff Koons’s artistic practice and that of a tradition inherited from pop art. Despite the differences, this reappropriation of ordinary objects in art is a political gesture also seen in the work by Nino Cais. It is a response to the plutocracy that defines the behavior of the art market, which is also anchored in Christian values. To delve deeper into this issue, see: FOSTER, Hal. O que vem depois da farsa? São Paulo: Ubu Editora, 2021, pp. 65–69.

-

Corporificar, 2023

Corporificar, 2023 -

Escavador, 2023

Escavador, 2023 -

![Meanwhile, the yearning to “become present” is announced in an artwork: by writing the word corporificar [embody] at floor level,...](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Untitled, 2023

Untitled, 2023 -

-

Near this installation, there is a large circle marked out by the presence of another group of plates, filled with powders of a wide range of foods and spices found in Brazil. The compacting of this material in the plates, bearing the outline of the map of Brazil in relief on their surface, brings to mind the political notion of place. This large circle, similar to Lygia Pape’s Roda dos Prazeres [Wheel of Pleasures] (1968), creates the conditions for a ritualistic environment where the formulation of our social body is shared in communion. This is, therefore, the exhibition’s epicenter, and is intentionally titled Querência (2023). Here, the term querência might be used in reference to this word’s two most well-known meanings: pastureland (the natural habitat of cattle), or a person’s origin or place of reference, insofar as one was born or raised there, or has resided there for a long time. The work’s aim therefore includes a profound desire for a link to the land in the sense of origin and destiny.

Based on these works with the soup plates, the artist represents and triangulates three different concepts/signs that are important to him: body, territory, and Brazil. They ultimately construct a form and idea of origin. We therefore see that in this gathering of seemingly very dissimilar works – and yet all very near to Nino Cais’s repertoire and experience – the artist invites us to partake in a fourfold action: remember and reconstruct, clarify and embody.

-

Untitled, 2023

-

![NINO CAIS [1969, São Paulo, Brazil . He lives and works in São Paulo, Brazil]. Selected solo exhibitions: Poema a...](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7)

Viewing room

![Effulgence The exhibition is titled Clarão [Effulgence] for various reasons that shed light on the conceptual core of the artist’s...](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_620,h_620,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/92bc8079ae68f53fd0edef5c2a6b08fbj.jpg)

![Untitled [series Sudário], 2023](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/338a509cd8606e7b919087c0579441d1j/casatri-ngulo-nino-cais-untitled-series-sud-rio-2023.jpg)

![Untitled [series Sudário], 2023](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/0312f7f341d6e7d3a25681e2e2a5f536j/casatri-ngulo-nino-cais-untitled-series-sud-rio-2023.jpg)

![Untitled [series Sudário], 2023](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/b730c57c771f0870ed82c45453a9a23aj/casatri-ngulo-nino-cais-untitled-series-sud-rio-2023.jpg)

![Untitled [series Sudário], 2023](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/76907ee650a9a39e6a56ac41e404539aj/casatri-ngulo-nino-cais-untitled-series-sud-rio-2023.jpg)

![Untitled [series Sudário], 2023](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/2c4e801fcca6ccd5ac817be073691d60j/casatri-ngulo-nino-cais-untitled-series-sud-rio-2023.jpg)

![Untitled [series Sudário], 2023](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/ad3a37bda478006b6cd92934df0beef0j/casatri-ngulo-nino-cais-untitled-series-sud-rio-2023.jpg)

![Untitled [series Sudário], 2023](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/6e0e9dd26ea1576116a8acde3f6080c9j/casatri-ngulo-nino-cais-untitled-series-sud-rio-2023.jpg)

![Meanwhile, the yearning to “become present” is announced in an artwork: by writing the word corporificar [embody] at floor level,...](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_620,h_620,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/casatriangulo/images/view/79618f4a2942236913d375919289adc6j.jpg)

![NINO CAIS [1969, São Paulo, Brazil . He lives and works in São Paulo, Brazil]. Selected solo exhibitions: Poema a...](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_620,h_620,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-artlogicwebsite0070/usr/images/feature_panels/image/items/c4/c43a3777e1b845abb971104e152ce5e0/whatsapp-image-2023-05-16-at-16.57.21.jpeg)