-

The oeuvre of Roberto Magalhães (1940–) is characterized by a distortion of the real, through which he makes us perceive how grotesque and yet paradoxically hilarious reality can be. The shapes of his characters, portraits, self-portraits, objects and landscapes appear dissolved, extended, contracted, monstrous, funny and notoriously out of order. They are fictional characters and scenes that nonetheless construct a strong associative link with reality. Indeed, fiction and reality do not find very clear distinctions in his work; they blend together, even as they complement and feed off one another.

-

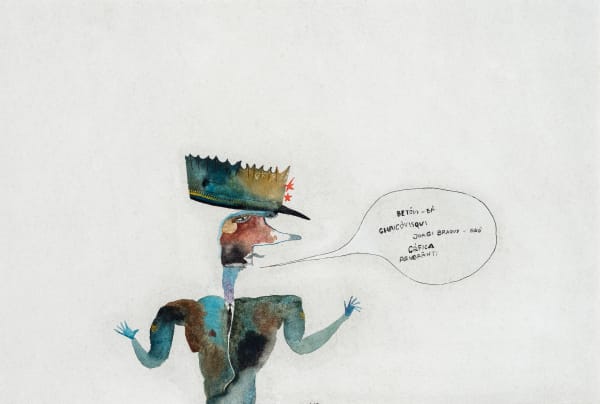

Auto-retrato falando, 1965

Auto-retrato falando, 1965 -

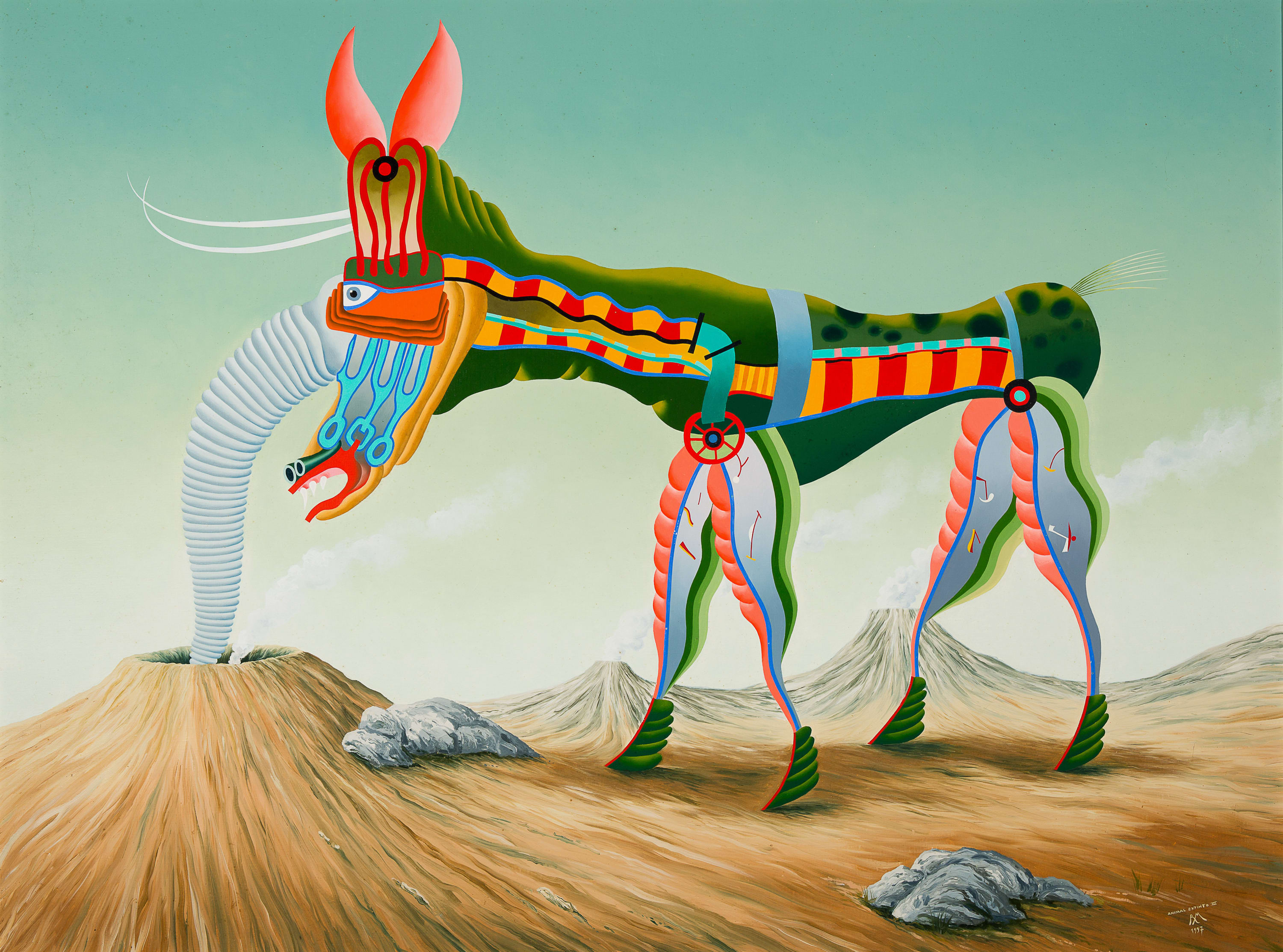

Animal extinto III, 1977

Animal extinto III, 1977 -

Art historiography has pointed to influences and interrelationships that Roberto’s work bears with surrealism. In my view, however, his work is more closely linked with the generation that followed surrealism, which looked at that art movement, especially Magritte, through new eyes, while adding references from a Brazilian context, particularly linked to caricature. But within that constellation he is outstanding due to his unique perspective. His work is not simply surrealist (“they are surrealist characteristics”[i]), because it always contains a dose of humor. Sometimes, the humor gives way to the tragic or combines with it, as in the case of the first block of works, made in the context of the dictatorship, throughout the 1960s.

-

"O carioca Roberto Magalhães, vencedor em Paris com seus desenhos". Fatos & Fotos, Três Vitórias de uma opinião, Esko Murto, 1965

-

In 1965 and 1966, Roberto was awarded a succession of prizes – besides the prize at the IV Paris Biennale and the award from the Jornal do Brasil, he received the Petite Galerie prize at the April Salon, granting him a solo show at that gallery, and also won the foreign travel prize at the 15th Salão Nacional de Arte Moderna (SNAM), in 1966. That prize allowed Roberto to travel to Paris in the following year, 1967, which saw another milestone in his career: his participation in the exhibition Nova Objetividade Brasileira, organized by Oiticica and held at MAM-Rio, at which museum he opened a solo show some months later. Nova Objetividade Brasileira was a singular show for presenting a survey of the vanguard trends then being created by Brazilian artists. The aesthetic proposals developed by the artists and explained in the catalog included not only the surpassing of easel painting, but also the viewer’s participation in the artwork, and the taking of political stands. The exhibition did not exactly present a unity but rather the plural and experimental character of two generations: that of the neoconcrete artists and that of Roberto’s generation, which arose amidst the early years of the dictatorship. His works in that period are characterized by graphic violence, with the increasingly substantial presence of monstrous beings in a silenced environment – a reflection of the tension that reigned at that time.

-

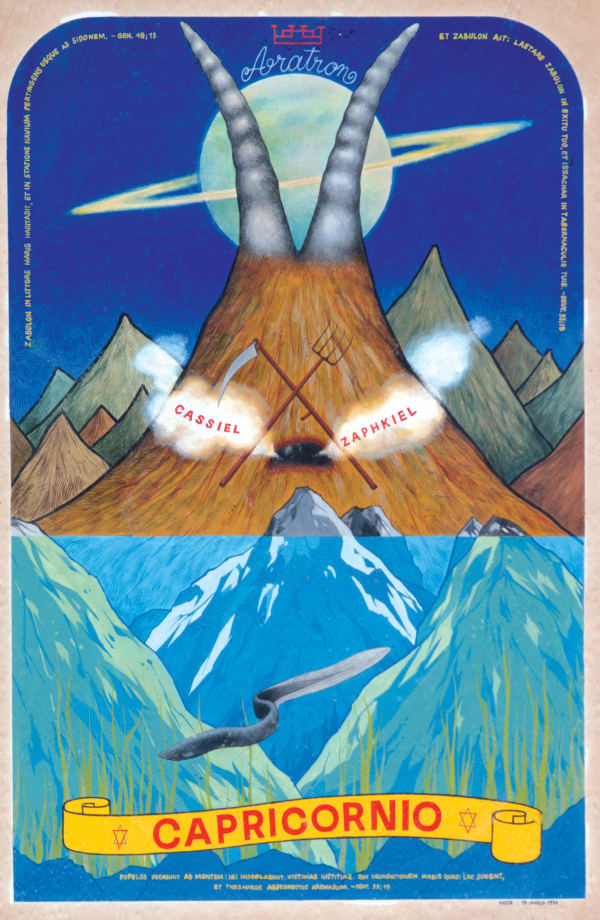

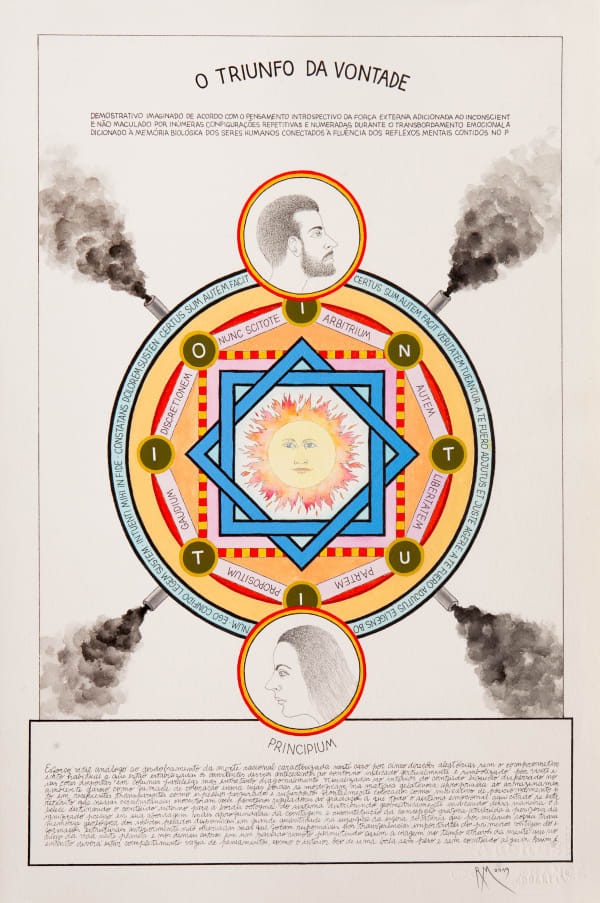

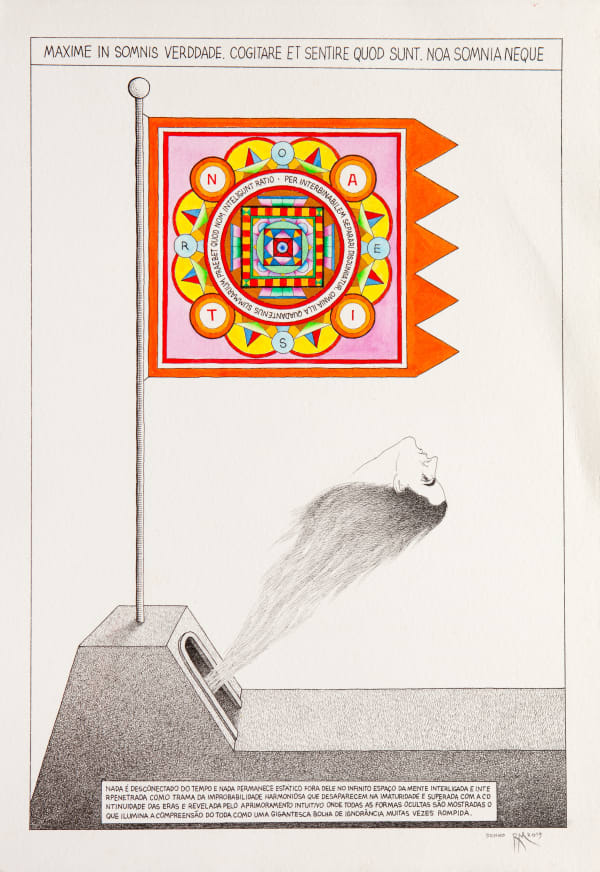

It Paris he met up again with Antonio Dias, a close friend with whom he shared the joys and hardships of living in Brazil under the military dictatorship, and of living abroad, and in 1968 he showed at Galerie Debret. That same year he returned to Brazil and found a country bearing the brunt of the oppressive Institutional Act #5 (AI-5) – an even more turbulent, violent and repressive place. The National Congress was closed, the communication media was under censorship, individual rights were suspended, and artists had become fearful of producing art. Roberto turned eagerly to occultism, Theosophy, and, above all, Buddhism, soon meeting the monk Anuruddha. In the district of Santa Teresa, in Rio de Janeiro, he helped to build the Meditation Center of the Buddhist Society of Brazil and resided there. He donated his material goods, he interrupted his artistic activity and spent six years without showing anything. I suppose that the then prevailing atmosphere of violence and indetermination was a key factor for Roberto’s going into a period of “spiritual reclusion.” In 1971, he gave an interview to the newspaper O Globo and explained that in recent years he had dedicated himself to studying what he called “esoteric art.” In October 1975 he wrote the text “Algumas considerações sobre a arte do futuro” [Some Considerations about the Art of the Future]. He positioned himself as a “mystic artist,” and, in an interview, argued that his production at that time “is not art in the traditional sense of the word.” And he continues: “I only use the abilities I have to represent spiritual things in drawing. Because form and color in the traditional manner they are used in art have lost meaning for me. Each line, a stroke in my current works, has a meaning.”[i] At that moment, symbols such as talismans and alchemical allegories became more intensely present in his art, along with written passages from ancient treatises of alternative medicine, often in Latin.

-

The 1970s also brought new contributions to culture. During the era of the Cold War, the Berlin Wall, dictatorships and the Vietnam War, the world also saw the rise of rock music, protest music, beatnik literature, the hippie movement, the birth control pill, macrobiotic diets and movements for civil rights of women and black people. This context had much to do with Roberto’s choice to delve increasingly into studies on spirituality as well as with his obsessive interest in alternative medicine.

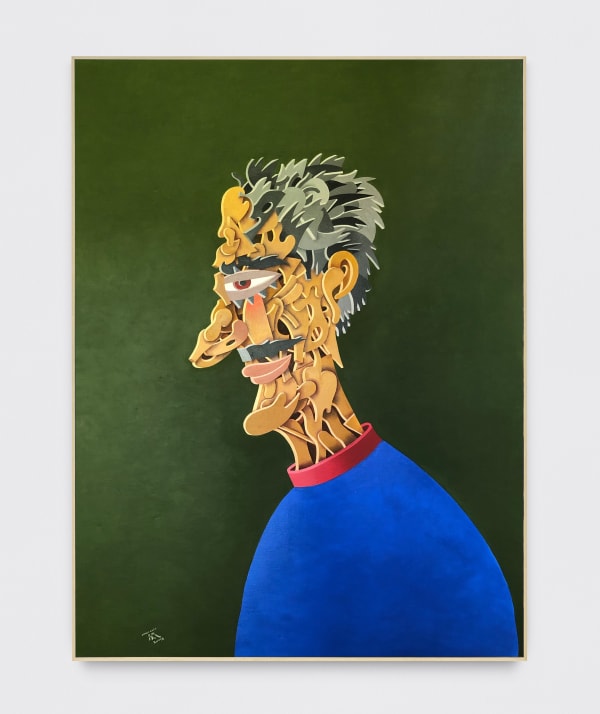

After four years at the Meditation Center, Roberto was strongly convinced of the idea that “if I was born with this skill [of art], I must manifest it. If not, how can I continue a spiritual life? […] There should be a balance between creativity and the yearning for spiritual life.”[i] He started showing his work again in 1974. From that moment onward, broadly speaking, we can divide Roberto’s interests as: the face as a space of dysfunction; the domestic space and a politics of the absurd; masking; and soft architecture. Mulher do Futuro [Woman of the Future] (1975) and Ministro do Tempo [Minister of Time] (1976) are works that represent the idea of dysfunction. The former presents the profile, in graphite, of a woman with an upside-down face. The nose, mouth, jaw and eyes are out of their normal places. The face, which particularizes and individualizes the subject, becomes an inhospitable and confusing terrain. There is something jocular in this operation that allows one to think of the rift of insanity as a symbolic component in Brazilian art. For its part, Ministro do Tempo obeys a similar logic, but with the face seen from a frontal perspective. In this case, the facial details are displaced by 90°, imparting an air poised between the strange and the comical. To comment on dysfunction – when, for example, the eyes no longer tell us clearly what is before us – is also to allegorically discuss the violence, repression and fear that Brazil was going through at that time. In a pastel work from 1978 this procedure is repeated with a character’s face displaced by 90°, but the figure in question is a man wearing a necktie. The referent lies within a narrower scope, as here we see the image of an executive or bureaucrat, a routine character at his work. There is a perversity in seeing this figure, linked to capital, all alone and “losing” his head.

-

Homem borracha, 1984

Homem borracha, 1984 -

Mulher na janela

Mulher na janela -

Ministro do Inferno, 1975

Ministro do Inferno, 1975 -

-

Untitled, 1985

Untitled, 1985 -

Central do Brasil (1983) and Seres urbanos (2001) belong to his field of soft architecture. Both depict contorting buildings that foreshadow tragedy, for example. But the tragedy takes on the airs of an animated drawing, a world where no one ever gets injured or dies. The buildings may wobble but they do not fall. Moreover, the characters in these two works transit through the soft city without concern. The most notable building in Seres Urbanos is the only sign of rigidity and inflexibility in the city where it seems that buildings are about to come tumbling down. Automobiles and pedestrians move through the same space since there is nothing separating them. Moreover, an airplane that looks like a fish is flying over the city’s erratic architecture. Incoherence is an everyday practice for inhabitants of big cities. We get used to what is different (aligned with the unreal or the fictional) even though we are unaware of this process.

-

-

Untitled, 1975

Untitled, 1975 -

The 1990s also saw continuity in Roberto’s research. His painting became increasingly absorbed in characters and landscapes that seem to float; they levitate as though weightless. In Coutinho’s analysis, “although some of his themes may appear dramatic, the mood of his drawing, due to his special lines and his reds, yellows and blues, is free from any anxiety.”[i]

Roberto’s most recent works have headed off toward a playful and fantastic universe. In some, we see the choice of mechanical shapes, with an industrial aspect that is nonetheless intensely colorful, set loose in space, creating their own rhythms, associating chaos with randomness. They look like mobiles guided by a motif that favors disorder. This ungroundedness, this choice to leave the forms floating as though they had a life of their own, with the color transforming into organic monochromes, is something the artist has been doing in recent years.

-

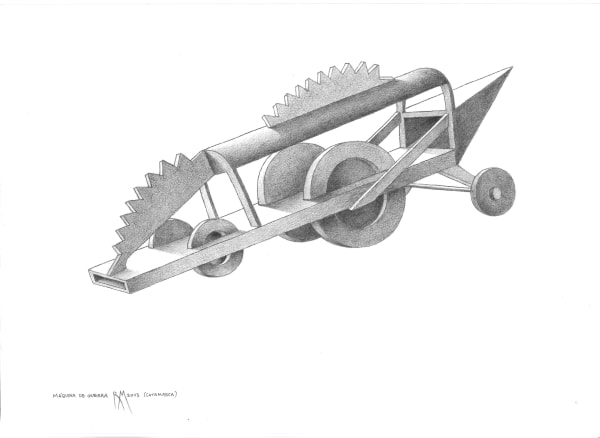

It is important to emphasize that his most recent production involves more than the theme of abstraction. Fish-airplanes, armored vehicles, architectural shapes like gates, pedestals and palaces are recurrent themes along with those linked to mysticism as seen in O Triunfo da Vontade or Sonho (both from 2019). In a recent series of works in ink, the artist seems to return to the theme of his sculptures created in the mid-1960s, like the large wooden revolver he showed at the exhibition Nova Objetividade Brasileira. The works Máquina de Guerra, Objeto desconhecido, Objeto do futuro convey a warlike and catastrophic sensation, despite their overall childish and playful aspect. It is hard to look at these drawings of machines or objects that tend toward annihilation and not think about the harshness of contemporary life. The typology of war that Roberto creates is to a certain degree linked to his time. Once again, the distinction between reality and fiction is thrown into suspense.

-

Roberto has constructed an autonomous place in Brazilian art, producing an oeuvre running against the grain of spectacularization and the schools that would otherwise delineate a style for his work. His politics is authorial and independent from any specific art movement. Under the shadow of the expressionism that marked his outset, he went through a period of insightful criticism of the dictatorship, with prints that evinced the acerbic humor that was to characterize him in the following years. The smile – an element of his work – is converted into a sneer, often at himself, as we see in an extensive production of self-portraits. In the 1960s the smile became a powerful mechanism of reflection on a terrified society, and in the 1980s – when we saw the beginning of a return to democracy, after a little more than 20 years of dictatorship – the smile continued being a weapon for the raising of awareness. Roberto’s work, and his jesting, therefore, circulate on this tightrope between tragedy and the smile, violence and mockery.

[1] Unidentified author. “Roberto Magalhães: Uma trajetória fantástica até o esoterismo.” O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, Cultura, May 21, 1975, p. 33.

[1] Magalhães, cited in JONES, Hildegard Angel. “Arte hermética.” O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, Geral, December 29, 1971, p. 4.

[1] Magalhães, cited in RANGEL, Maria Lucia. “Roberto Magalhães.” Jornal do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, August 6, 1975.

[1] COUTINHO, Wilson. “O drama e o humor fino convivem num traço liso.” O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, Segundo Caderno, November 19, 1996, p. 10.

-

Viewing room