-

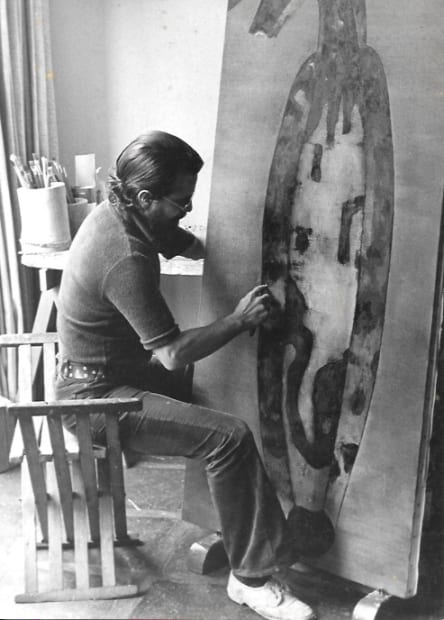

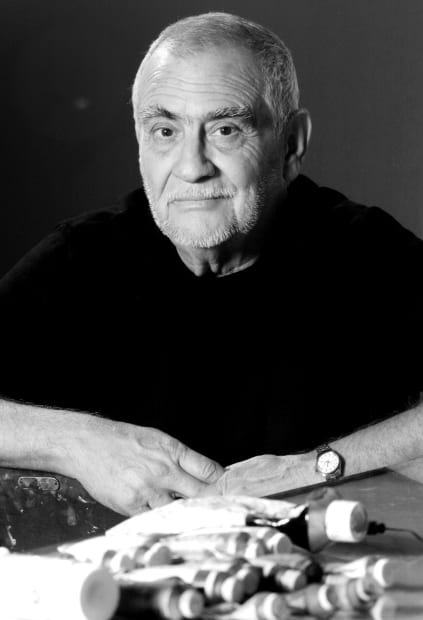

Antonio Henrique Amaral brought a singular voice to Brazilian and Latin American art of the second half of the 20th century. Born in 1935, he was part of the generation that came into its own under the authoritarian rule of the military dictatorship installed in Brazil in 1964, having produced some of the most incisive allegories from that period. His visceral work dealt with political violence, existential discontent and erotic desire with the same intensity. His experimental approach challenged hackneyed lemmas concerning chromatic composition, the treatment of surfaces and stylistic cohesion. His blend of visceral attitude with experimental daring makes him not only a key figure in the history of Brazilian and Latin American art, but also an influential artist for the young generations that defy normativities and authoritarianisms.

-

-

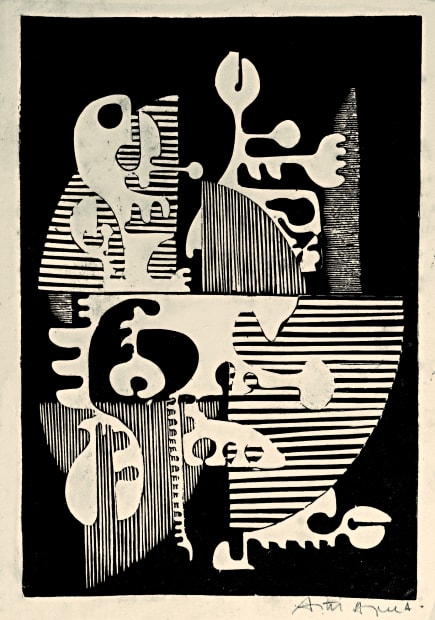

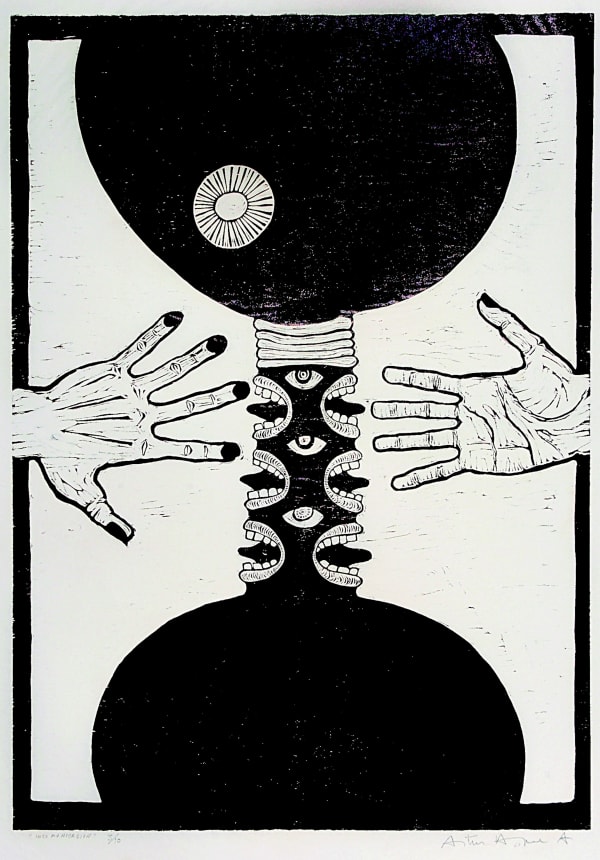

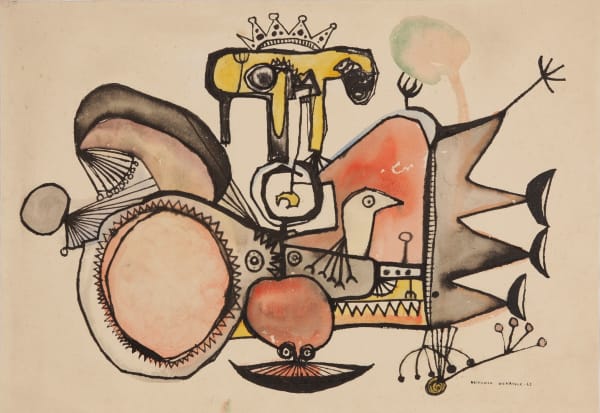

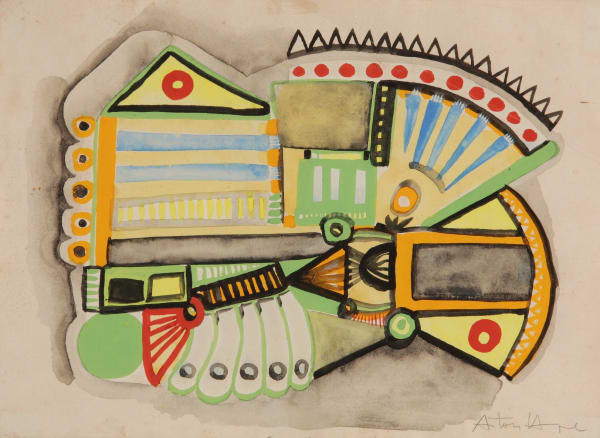

In these experiments, the artist evinced few indications of being especially concerned about the fierce debates around the constructive abstract trends and the social ballast legated by modernism. Even his drawings from that time alternated freely between figuration and abstraction, maintaining formal instability and visual restlessness as constants. It seems that the artist was committed to finding translations for anxiety, and he demonstrated an interest in the ineffable, the strange, the desiring entity and the unnameable.

-

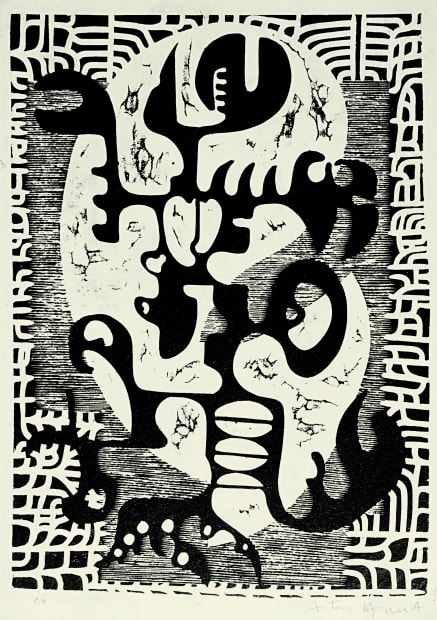

DAS BOCAS, 1967

DAS BOCAS, 1967 -

Due to the consistency of his production, Amaral was rapidly introduced to the Brazilian art scene, holding his first solo show, featuring prints, at MAM-SP in 1958. That same year, he traveled with his works to show them in Chile and wound up being invited by the Organization of American States (OAS) to show at the Pan American Union (Washington, D.C.) in 1959, receiving a grant from the Ingram Merrill Foundation to attend the Pratt Graphic Art Center (New York, NY). In that brief period of time, he strengthened his bent for plenty of international transit, especially between North and South America.

HIS ACTIVITY IN THE EARLY 1960S WAS LIKE THAT - INTENSE AND INTERNATIONAL. IT WAS PERHAPS IN THAT PERIOD, DUE TO HOW THE UNNAMEABLE BEINGS IN HIS WORKS BEGAN TO FORM A SORT OF A BESTIARY - THAT ANTONIO HENRIQUE AMARAL GAINED THE FEATURES THAT CAUSED HIM TO OFTEN BE ASSOCIATED TO THE TERMS "MAGICAL REALISM" AND "FANTASTIC REALISM," WHICH WERE COMMON IN THE DEBATE OF 20TH-CENTURY LATIN AMERICAN LITERATURE. THE NEXUS OF THIS ASSOCIATION LIES IN THE ARTIST'S WILLINGNESS TO GO BEYOND THE NATURALISM OF REPRESENTATION AND TO EVOKE IMAGINARY SITUATIONS AND BEINGS. AS IN ALL FANTASTIC REALISM, HOWEVER, SUCH EXTRAPOLATIONS OFTEN INCREASE THE EFFECT OF VERISIMILITUDE INSTEAD OF DIMINISHING IT - ESPECIALLY WHEN REALITY ITSELF SEEMS DIFFICULT TO GRASP.

-

The challenge to grasp the real was imposed on Amaral in 1964. With the coup d'état that interrupted the fragile Brazilian democracy, the fields that held the most imminent potential for progressivist social transformation - education, agrarian reform, political party organization - were violently repressed, leaving it up to cultural production to take up its role as a channel of social criticism against the growing authoritarianism. This narrowing of the traditional political practices, in conjunction with the iconoclast vitality of the countercultural youth of the 1960s, led to the strengthening of the idea of opinião [opinion], a word which, not by chance, was adopted at that time as a title for shows, a theater company, a cultural fair, art exhibitions, and even a newspaper.

Antonio Henrique Amaral, who from early on took the technical material development of his production as a process aimed at modifying the inner conflicts in his works, then responded to the ethical imperative that mobilized a large part of his generation: that of issuing critical opinions to confront the military regime and its ideological propaganda.

-

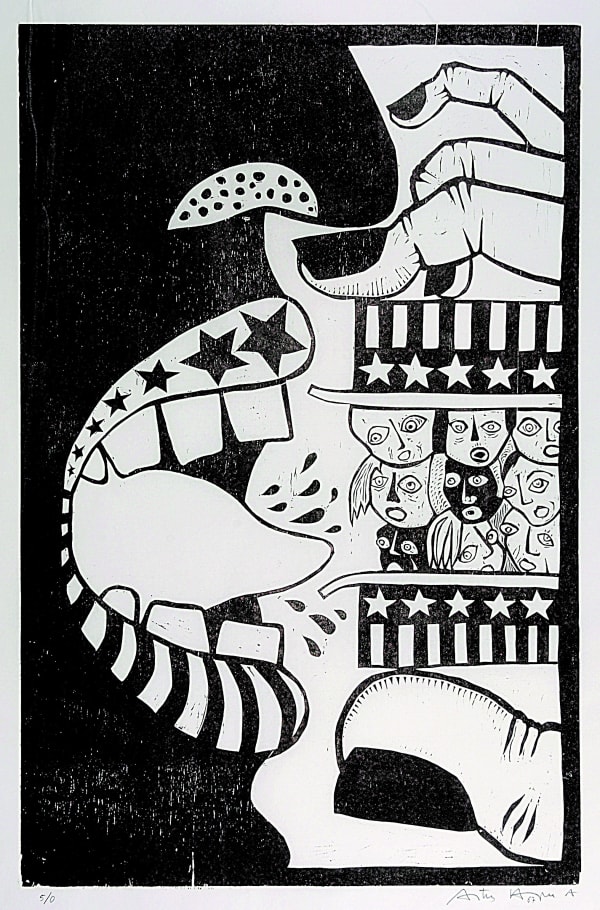

To this end, he possessed an excellent language for the spontaneous expression of criticism, satire, and provocations. Woodcuts can be made quickly, they are reproducible and are associated to the practices that overflowed from the repertoire of modern art. As though seeking to underscore this vocation for printmaking, Amaral began to observe the woodcuts that illustrate the cordel booklets in the popular tradition of the Brazilian Northeast and assimilated some of their typical features. He distanced himself from the existential symbolisms, his line became drier, he simplified his treatment of hachures, and made his characters recognizable as allegories of the country’s political affairs and everyday life. With no fear of using immediately readable symbols, he tried to go directly to the core of the contradictions of his time.

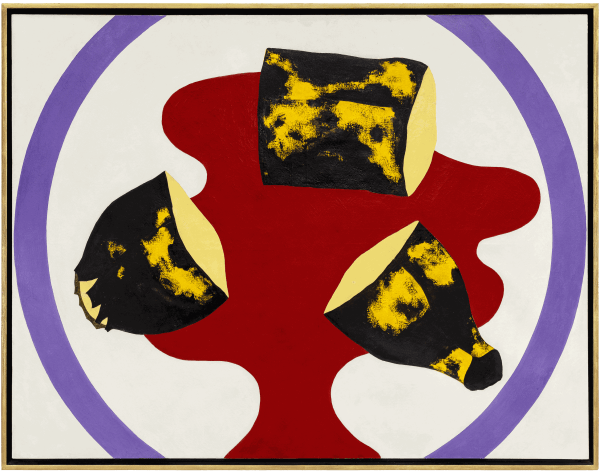

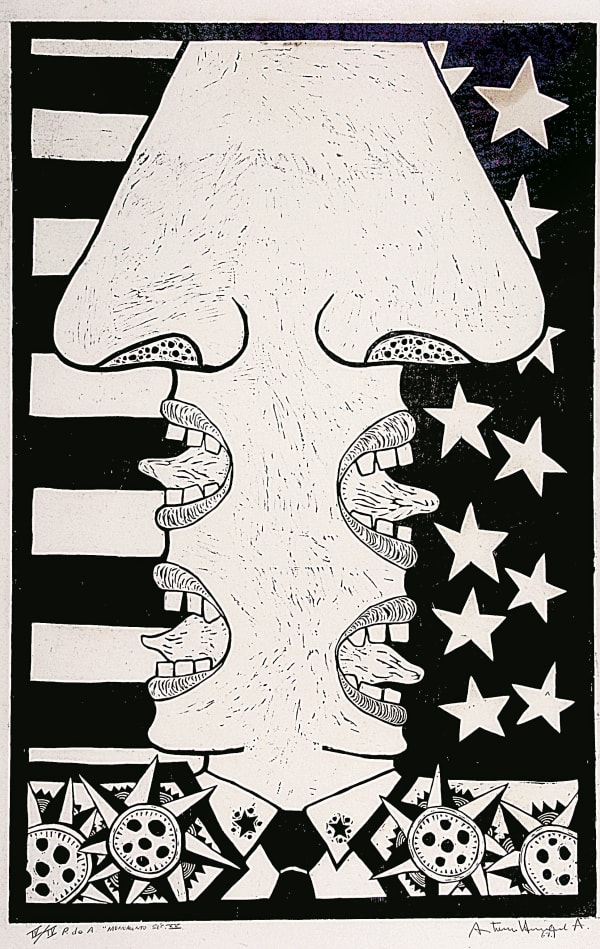

The album O Meu e o Seu (1967) was treated by Antonio Henrique Amaral as a work that summarized all of his development in woodcut. His polychrome prints offer allegories of contemporary life in Brazil, reflecting on communicational impasses, feelings of isolation and authoritarian actions. In them, there are oversized heads, two-faced military officers, crushed masses and isolated subjects, as well as mouths, many wide-open mouths with visible teeth and a moving tongue. They are allegories of incommunicability, where everyone is talking, but no one is listening.

-

Although he did not participate in the show Nova Objetividade Brasileira (MAM-Rio, 1967), Antonio Henrique Amaral’s production has relevant points of contact with that event’s aim to communicate “living thoughts,” as Hélio Oiticica stated. Within the many voices that were heard in Brazil during the 1960s and 1970s, Amaral’s is one of the most acerbic and visceral. It was not a matter of only pointing out the villains – something easy to do at the time, just as it is today – but to give form to the disgust brought on by injustice and by the fraying of the social fabric. The wide-open mouths made by the artist talk too much and no one listens. They shout, they order and emit droplets of spittle while their bearers become more and more dysfunctional. Among Amaral’s tongues, bananas, forks, beasts and generals there is a constant flirt with the grotesque that is perhaps the most fertile aspect of his work when seen today.

-

Amaral kept up his commitment to find impactful and multifaceted ways to communicate critical positions concerning the directions of the country even when the receptivity for this became more violent. The year 1968 was the peak and rupture for the countercultural production that then spanned from theater to music and included theater, poetry and the visual arts. In reaction to the growing societal movements, the military regime increased its practices of censorship and, with the promulgation of AI-5 in December 1968, assumed its dictatorial character, suspending the freedom to express political opinions. In that period, Amaral was working on changes in the scale and dynamics of his activity. He became systematically dedicated to painting, a medium he was still not familiar with. Initially, he brought to it the same symbolic universe he had gathered in his prints, which became more frenetic and abject with the colors and lines of his experimental painting. At the end of the 1960s, although still a young artist, he was already recognized as an exceptional printmaker, while painting offered him entirely new challenges. In the first years of complete dedication to painting, Amaral transplanted many of the themes of his woodcut to small and medium-format canvases, exploring new colors and gesturalities. This exercise soon resulted in perturbing images, open to multiple interpretations.

-

Boa Vizinhança, 1968

Boa Vizinhança, 1968 -

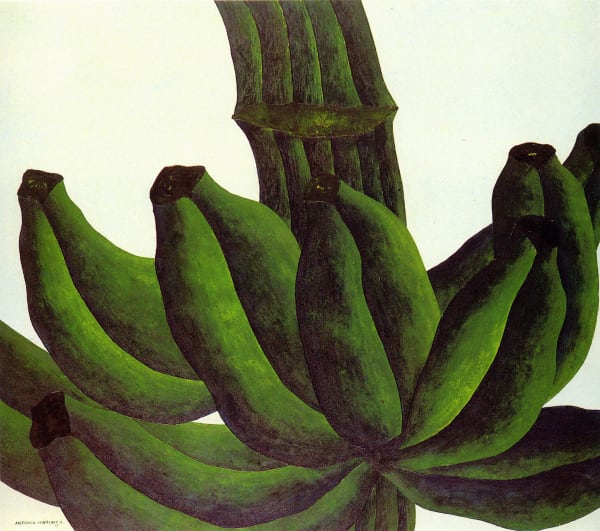

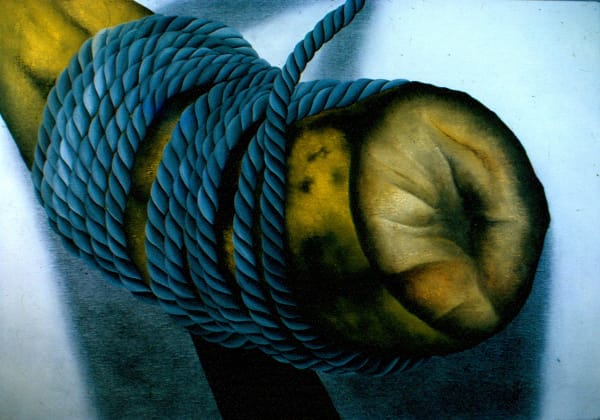

While the bananas appeared in Antonio Henrique Amaral’s painting in a graphic and schematic way – similar to how he painted mouths, insignias and flags – the artist soon began to use them as models for a more languid and realistic painting. Using photographs and successive sketches, he studied framings, compositions, shadowings and even details of the spots on the banana peels and of the viscosity within the bananas. His direct observation of the fruits, extended and reframed by photography or by drawing, was his starting point for the paintings. Shapes and arrangements were thus defined, then elements would be added and simplified during the process of painting the canvas, in accordance with pictorial taste and the possibility of “unseeing” or “seeing through” the bananas, seeing them as successive rhythms of colors and spots. Simultaneous with this tactile and visual approach, these fruits underwent a semantic expansion when the artist decided to approach the Brazilian context that followed AI-5 and used them as surrogates of the victims of the state’s arbitrary violence, pictorially substituting them for the bodies of young people tortured and executed by the government.

-

THE MAIN OUTCOME OF THIS PROCESS WAS SEEN IN THE SERIES CAMPO DE BATALHA, PRODUCED IN 1973 AND 1974 IN NEW YORK. THE LABORIOUS PAINTINGS OF THAT SERIES HAVE LARGE DIMENSIONS AND SPECIAL DETAILING IN THE TEXTURES AND EFFECTS OF SHADOWING, WHICH IMPART A SYNESTHETIC QUALITY TO MULTIPLE SITUATIONS OF THE CUTTING, TYING UP AND PIERCING OF RIPE BANANAS BY FORKS AND ROPES. THEY ARE, SIMULTANEOUSLY, REFERENCES TO VIOLENCE AND PICTORIAL SENSORY EXPERIENCES THAT SOMETIMES BORDER ON THE EROTIC.

-

It was also in New York during the 1970s that Amaral contended more directly with his identity. The contrast with the North American artists and the dialogues that he found more easily made it clear that he would always be understood as a Brazilian and/or Latin American artist, but also alerted him to the importance of striving for values and meanings that overflowed the geopolitical reference of their origin. He seems to have solved this impasse through dialogue. The many letters that the artist kept include a noteworthy, frank and intense correspondence with Ferreira Gullar. The poet and critic had written about Antonio Henrique Amaral on other occasions and had gone through a violent process of successive exiles (in Russia, in Chile, in Peru and in Argentina), during which he continued his conversation with Amaral about the directions and lack of direction of the South American continent. Reflections on form and politics, everyday life and resistance marked this exchange, giving Amaral a basis for continuing to discuss the political and social reality of his country, yet remaining aware that his work could gain broader or extemporaneous readings.

-

There is a dialogue that Amaral remembered various times, which arose when he showed his production to his somewhat distant relative Tarsila do Amaral, who, already at an advanced age, told him something like: "Interesting, very interesting for you to study painting through the banana." He agreed with this observation, as he understood that his work had concerns (and obsessions) that went beyond the desire to manifest opinions and to respond to political contexts. Indeed, as the military dictatorship headed toward the gradual - and until today incomplete - reinstallation of the constitutional democratic bases, Amaral gave vent to other aspects of his existential uneasinesses and his pictorial desire.

-

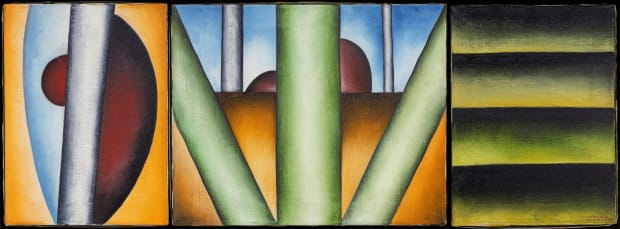

FROM THE LATE 1970S ONWARD, ANTONIO HENRIQUE AMARAL'S PRODUCTION NO LONGER RESORTED TO ALLEGORY AS ITS PREDOMINANT SYMBOLIC MODEL. THERE WAS STILL SPACE FOR METAPHORS AND SYMBOLISMS - FOR EXAMPLE, IN HIS ADHESION TO THE DENOUNCEMENTS OF THE BRUTAL CUTTING DOWN OF THE BRAZILIAN FORESTS - BUT THE ARTIST'S POSTURE TENDED TOWARD THE CONSTRUCTION OF DREAMLIKE SCENES AND TO THE INTERLINKING OF ABSTRACT RHYTHMS AND COLORS. IT WAS THEN THAT DRAWING, WHICH WAS ALWAYS HIS MOST FLEXIBLE AND WIDE-RANGING CREATIVE PROCESS, ASSUMED A REDOUBLED IMPORTANCE. -

-

TRÍPTICO, 1980

TRÍPTICO, 1980 -

In these exercises of the imagination, the artist got the opportunity to push his handling of shadowings and relationships of chiaroscuro to the state of paroxysm. He was also able to explore rare chromatic combinations, and sometimes vibrant and diversified palettes that refer to Tarsila’s most colorful works.

-

When one observes Antonio Henrique Amaral’s oeuvre as a whole it is plausible to think of it as a bestiary expanded in time and space: a succession of forms and figures that defy human identification and its capacity for communication, or, in a complementary way, a landscape of inanimate objects that he imbues with an empathic identification. There is still much to discover and debate about in his work, especially now, when at every point and place there is a search for examples of artworks able to resist not only the authoritarian projects now underway, but also the normativities that restrict the understanding of the nature of desire, sexuality and communication.

-

OS CORPOS E A LUZ, 1996

OS CORPOS E A LUZ, 1996 -

-

AS A RESPONSE TO THE MILITARY COUP OCCURRED IN BRAZIL IN 1964, AMARAL STARTED TO DEVELOP EXPLICITLY A POLITICAL WORK WITH A SATIRICAL TASTE, INCLUDING ELEMENTS OF POPULAR AND MASS CULTURES, IN WHICH HIS SET OF WOODCUTS, ENTITLED O MEU E O SEU (1967) WAS HIGHLIGHTED AT MIRANTE DAS ARTES (SÃO PAULO), GALLERY IN WHICH PIETRO MARIA BARDI WAS PARTNER. THE PERIOD ALSO MARKED THE BEGINNING OF HIS PAINTING WORK, HAVING BEEN CARRIED OUT BETWEEN 1968 AND 1975 HIS EMBLEMATIC SEQUENCE OF CANVAS THAT PROBLEMATIZE THE MOTIF OF BANANAS AS A NATIONAL SYMBOL. AT SALÃO DE ARTE MODERNA DO RIO DE JANEIRO IN 1971, HE WAS AWARDED WITH A TRAVEL TO ABROAD AND WENT TO NEW YORK, FROM WHERE HE RETURNED TO BRAZIL IN 1981. ANOTHER HIGHLIGHT OF HIS TRAJECTORY IS THE PAINTED WALL ENTITLED SÃO PAULO – BRASIL: CRIAÇÃO, EXPANSÃO E DESENVOLVIMENTO (1989), INSTALLED IN THE MAIN HALL OF PALÁCIO DOS BANDEIRANTES - THE STATE OF SÃO PAULO GOVERNMENT HEADQUARTERS, RESULT OF A CONTEST.

Over the course of more than six decades of artistic trajectory, Amaral has presented his work in several individual and group exhibitions both in Brazil and in countries of Latin America, North America, Europe and Asia.

His works are part of several important public collections in Brazil and abroad, such as: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET), New York, NY, USA; Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, USA; Art Museum of the Americas (AMA), Washington, D.C., EUA; Casa de las Américas, Havana, Cuba; Instituto de Arte Latinoamericano (IAL), Santiago, Chile; Latin American Art Collection, Essex University, Essex, England; Museo de Arte Americano de Maldonado (MAM), Maldonado, Uruguay; Museo de Arte Moderno de Mexico (MAMM), Mexico City, Mexico; Colleccion FEMSA, Monterrey, Mexico; Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogota (MAMBO), Bogota, Colombia; Museo Nacional de Arte (MNA), La Paz, Bolivia; Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo (MAC-USP), São Paulo; Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM-SP), São Paulo; Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), São Paulo; Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ), Rio de Janeiro and Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo.

His work has been extensively discussed by Brazilian and international critics and curators, such as Paulo Miyada, Aracy Amaral, Jacqueline Barnitz, Damián Bayón, Sheila Leirner, Geraldo Ferraz, Vilém Flusser, Benjamin Forgey, Carreira Goldman, Shirreira Goldman, Frederico Morais, Roberto Pontual, Bélgica Rodríguez and Edward J. Sullivan.

![UM + UM = DOIS, 1967 xilogravura [woodcut], 32,2 x 42,5 Álbum O MEU E O SEU](/lib/archimedes/images/shim.gif)